Part 1 - Looking for the Origins of Independent Film Exhibition in Leeds

By Alice Miller

Welcome to the first in a new series of blog posts sharing my research into the history of independent film exhibition in Leeds. Focusing on several pivotal moments, such as the formation of the Leeds Film Group, the emergence of arthouse cinemas in Leeds, and the establishment of the Leeds International Film Festival, to name a few, my research investigates the practice and development of independent film exhibition in the city. I hope to shed light on a vital strand of our film culture and heritage and I’ll be sharing some of my findings over the coming months here on the Leeds Film website.

One might think this history begins with Louis Le Prince, the pioneering French inventor who captured the world’s first moving images here in Leeds. Despite Le Prince's monumental achievement, he was never able to exhibit his films and inventions to an audience and film exhibition developed in his absence. Le Prince’s work forms part of a vital pre-history to my research, and he sits within the early cinema history of inventions, machines and new technologies.

The history I’m concerned with has its roots in a film culture that began to take shape from the 1920s onwards, an emerging culture of exhibitors, filmmakers and critics who considered film as a serious art form and sought to foster its intellectual appreciation. The origins of independent film exhibition in Britain are often credited to the film society movement, with the first such society established in London in 1925. The film society movement championed film as a serious artistic medium, worthy of study and appreciation, and its work developed in tandem with the first stirrings of film criticism and studies in Britain. Independent exhibitions sought to provide an alternative to the commercial cinema industry and its over-reliance on Hollywood product, giving opportunities to see films that would otherwise not be seen. The rejection of Hollywood cinema corresponded with a desire to access more international cinema, follow new developments in artistic filmmaking, and reappraise the aesthetic merits of silent cinema (particularly German, French and Russian). The early manifestations of this movement are inescapably marked with elitism, with the London society largely comprised of London’s intelligentsia and seeking to cultivate small members-only groups of ‘discerning’ and ‘intellectual’ viewers.

Searching for the origins of this alternative film culture in Leeds led me to the Alec Baron archive in the Special Collections of the University of Leeds. Baron was an instrumental figure in the development of film exhibition in the city and his archive, which contains film programmes, flyers, periodicals, correspondence, personal writings, press cuttings and much more, is a rich and invaluable resource on the history of Leeds independent film exhibition. A different kind of pioneer to Le Prince, Baron was also involved in several film firsts, the earliest being the establishment of the first film society in Leeds in 1930. Baron would then play a role in bringing the first Repertory Cinema outside of London to Leeds. He was an active member of the film society movement and made close links with the British Film Institute from its inception, firstly with the Leeds Film Society Institute, and later with Leeds Film Theatre as part of the BFI’s Regional Film Theatre network.

Baron was born in Leeds on 29th November 1913, to Russian Jewish parents who had fled the pogroms as refugees, and was the youngest of four siblings. His earliest encounters with film were taking his mother to their local cinema and reading her the intertitles as she couldn’t read English. As a young man, Baron had aspirations to become a film director but relinquished them to stay home and help with the family tailoring business. Giving an outlet to his creative ambitions, Baron co-founded the Leeds Jewish Film Society, an amateur filmmaking club (a selection of his films are now housed in the Yorkshire Film Archive and you can view some of them via their website here).

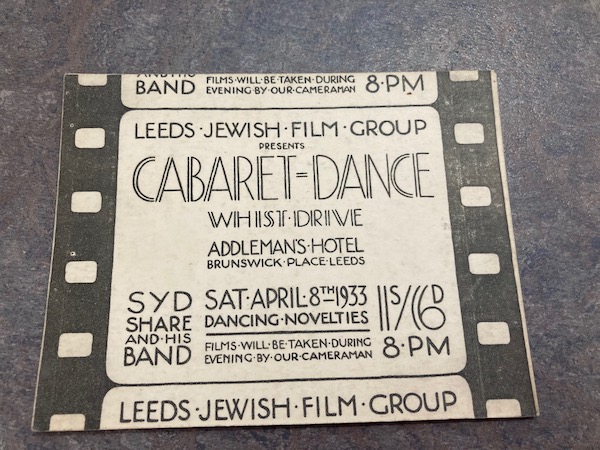

Leeds Jewish Film Group Cabaret and Dance Invitation Card, 1933

(Alec Baron Archive, University of Leeds Special Collections)

Beyond film, Baron’s other main passion was theatre, and there is an equally large collection of material in the Special Collections relating to Baron’s theatrical activities. Active in both the amateur and professional theatre communities of Leeds, Baron wrote and directed many plays, was a founder member of Leeds Unity Theatre (inspired by the leftist Unity Theatre in London) and later the Proscenium Players, the first Jewish Amateur Stage Group in Leeds. Baron was involved in the creation of Leeds Playhouse, leaving the family business to become its first Administrator and later wrote television screenplays, including for Coronation Street and The Two Ronnies. Baron was well immersed in the cultural life of the city and an important contributor to that culture. An in-depth look at Baron’s wider contributions to theatre and Leeds culture is beyond the scope of this project but I hope that future researchers will take up the challenge.

I will be exploring different threads of Leeds’ film exhibition history in the coming posts, including many that intersect with Baron, but for now, I will focus on the formative activities of the Leeds Film Group. Here I mainly draw on two pieces of writing in the Baron archive, an undated and untitled text by Baron that describes the origins of the Leeds Film Group (possibly written for the 50th anniversary of the film society movement), and his unpublished memoir written in 1991. The Group was born out of a band of school friends who had bonded over their love of the arts. Forming a secret club, the ‘Dramatic and Arts Club’, eight boys met after school in alternating living rooms to discuss the extra-curricular things they had read and seen, occasionally inviting outside speakers to join. This adolescent arts club ran for several years before film became their main focus. In his unpublished memoir, Baron described their growing interest in film:

Three of us, Leonard Rosenthal, Gersh Crawford and myself, had become very interested in the cinema as an art-form and had studied it closely, particularly under the influence of Paul Rotha’s remarkable book THE FILM TILL NOW, which Leonard and I had each bought with money we won in a newspaper “Spot the Stars” competition in which film actors had to be identified from a shot of the back of their left ear or in a strange make-up. This was the first book which discussed cinema as an art form rather than as entertainment.

Paul Rotha was a key figure in the British documentary film movement, alongside John Grierson and Basil Wright, and Rotha’s early critical writings on film would prove influential for the film society movement, early independent exhibitors, and art-minded cinema-goers, providing a guidebook for these young film enthusiasts. Rotha was also an advocate for alternative film exhibition and he campaigned for a dedicated art cinema in London, leading an organisation called the ‘Film Group’ (which perhaps inspired the naming of Leeds Film Group).

Along with Rotha’s foundational writings on film, Baron and his cohort were spurred on by Pathé’s new 9.5mm film format, an affordable format aimed at amateur filmmakers and film enthusiasts. The Group were keen to take advantage of the small gauge films released by the UK arm Pathéscope Ltd, which included many German and French silent classics they were eager to see. Differing from their London counterparts, the Leeds Group were not from wealthy families. Lacking the funds to hire the films and equipment, the Group decided to expand their members and garner interest for paid film screenings in order to cover costs. Screenings were held on Sundays and were members-only, as Baron writes:

Sunday film shows were against the law in Leeds, so we had to form a club. We hired a basement room under a synagogue at the corner of Exmouth Street and Camp Road for a season of Sunday night film shows and called ourselves, for this purpose, THE LEEDS FILM GROUP. Then we set about getting members.

Baron recalls “the year must have been 1930”, and thus began the first film society in Leeds, and some of the earliest independent film screenings in the city. The streets mentioned by Baron no longer exist but were in the Little London area of Leeds.

(The building on the left sits at the junction of Exmouth Street and Camp Road and was used as a synagogue in the 1930s so this is likely to be the first venue of the Leeds Film Group.) Undated photograph from the 1950s. West Yorkshire Archive Service, Leeds, LC/ENG/CP/27/1, no. 42

Reading Baron’s writings, it is clear that considerable love and care was taken to present the films and he remarks “we had great reverence for the films we showed”. The Group used a home-made screen, decorated the space with film memorabilia, carefully selected and played musical accompaniment for the films, and prepared introductory talks. They each had assigned jobs in the group - “two on projection; two on music; two on screen erection, masking out and room decoration; two on front-of-house and membership.” Reflecting on these early screenings, Baron writes:

We sold out every performance - even standing-room on some occasions - somewhere between sixty and eighty people per show. The audience was 70% Jewish. Many may have come because it was a Sunday night and there wasn’t much to do on Sunday nights, but they were amazingly enthusiastic and clearly impressed by what I look back on now as the sheer professionalism of the presentations.

Baron recalls some of the films screened at this primary venue: The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, both parts of Lang’s Die Nibelungen: Siegfried and Kriemhild's Revenge, Michel Strogoff - a French-made film directed by Russian filmmaker Viktor Tourjansky, the E.A Dupont directed films Vaudeville, Moulin Rouge and Piccadilly, René Clair’s The Italian Straw Hat, and German films Manon Lescaut and The Prisoner’s Song. All were silent films from the 1920s, and were made by either French, German or Russian filmmakers, with several produced by Erich Pommer. Though all the films are mentioned in Rotha’s The Film Till Now, the selection was perhaps more likely dictated by what was available on 9.5mm from Pathe. Following Baron’s mention of 1930 as the Group’s formation year, no date for the first season is specified, but it seems likely that it happened sometime between 1930 and 1932.

After this successful first season, the Leeds Film Group moved to a larger space in the Herzl-Moser Institute at 17 Brunswick Street, which seated around 100 (Brunswick Street no longer exists, now on that location are the infamous North Crescent flats). Having exhausted the Pathe 9.5mm films of interest, and with a lack of suitable films on 16mm, the group made the ambitious transition to 35mm, purchasing second-hand projectors from a local cinema (the Miners Institute on York Road). This upgrade in equipment meant they had to comply with safety regulations due to the highly flammable nature of the nitrate film stock. Unable to house the projector in the required fire-proof metal or teak box, their ingenious solution was to situate the projectors outside the building under a tarpaulin, projecting films through a slot in the window at the back of the room.

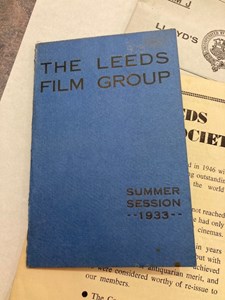

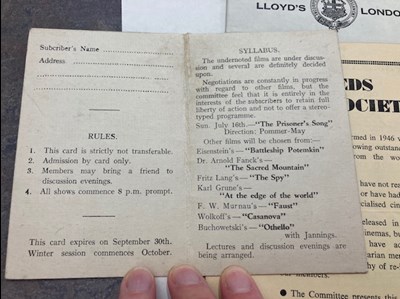

Baron describes their second season as another sold-out success and mentions some of the films screened at this venue, they included the UFA produced German silents At the Edge of the World, The Wonderful Lies of Nina Petrova and Fritz Lang’s The Girl in the Moon, as well as the Soviet documentary Turksib, and the French short film Pacific 231. In the archive is a small blue membership card that contains details of their ‘Summer Session 1933’ at the Brunswick Street space. They describe the film programme as a ‘Syllabus’, indicating that they presented these films for study and discussion, and delineating their activities clearly from those of entertainment. The card advertises a screening of The Prisoner’s Song on Sunday 16th July, and lists a selection of possible future titles. Further reflecting their educational aspirations, the card also mentions lectures and discussion evenings.

Leeds Film Group Summer Session 1933 membership card (Alec Baron Archive, University of Leeds Special Collections)

A prominent feature of early independent exhibition was its commitment to screening what was considered ‘art cinema’, what would later be referred to as ‘arthouse’, ‘specialised’ and ‘cultural’ cinema. During these early years, the films shown by societies and independent exhibitors were also commonly referred to as ‘unusual’ films. This descriptor appeared frequently throughout the Baron archive, on film society and cinema ephemera, and was perhaps a handy way to describe the sorts of films overlooked by the commercial cinemas, passed over because of their limited box office appeal and evoking their difference from the norm. With ambitions that mirrored those of The Film Society London, the Leeds Film Group aspired to provide a home to these ‘unusual’ and alternative films rejected by the commercial cinemas. In a Yorkshire Evening Post article from July 1933 under the headline ‘Unusual Films May Pay’, and the subheading ‘Films For the Few’, the journalist describes such an instance, writing “Karl Grune's thought-provoking production ‘At the Edge of the World, which was crowded out of the commercial cinemas because it was regarded as a doubtful ‘box office proposition’ is to be presented by the Leeds Film Group at their private theatre 17. Brunswick Street, Leeds, tomorrow (Sunday) night at eight o'clock.” The writer goes on to bemoan that “this crowding out of unusual films tends to a monotony in cinema entertainment which is more pronounced at the present time than in silent film days” (YEP 29 July 1933).

In a Yorkshire Evening Post article from the following month it was reported that “The Film Group at present are concentrating on preparations for an extensive and ambitious winter season. They are in negotiation for a fully equipped private theatre of much larger dimensions than the one in use now. The season will extend from October till March” (YEP 26 August 1933). The theatre was the Academy Cinema on Boar Lane (formerly the Savoy). With their membership ever expanding, and not wanting to turn new members away, the Group decided to approach a local cinema as a venue for their members-only Sunday screenings, and to screen with orchestra accompaniment. They planned to open their winter season with a screening of Waxworks, using a print they had remarkably recovered in a London junk merchants.

The Academy Cinema in Leeds launched in September 1933 and was a branch of the famous repertory cinema the Academy in London, an association that the Leeds Film Group had a hand in brokering (a detailed look at the Academy Cinema Leeds is coming in my next post). The first mention of the Group’s partnership with the Academy in London appeared in the Yorkshire Evening Post in July of 1933, with an article announcing that “A band of earnest students of screencraft have formed a society to be known as the Leeds Film Group, and they aspire to work in harmonious connection with the Academy Cinema. Oxford Street. London, which is acting as the centre of the repertory cinema movement in England” (YEP, 01 July 1933). The full Film Group press release on which this YEP article draws is in the Baron archive and throws further illumination on their ambitions, which included the screening of silent and sound classics that would otherwise not be seen and to form “a strong nucleus of appreciative followers”. From this strong nucleus they wished to build an active film society, operating from their own private theatre one day. The article appears to be aimed at drumming up interest for the Group and their summer season.

Regrettably, the ambitious winter season planned for the Academy never took place as the Group was denied permission by the local authorities, at the behest of the Cinematograph Exhibitors Association. Baron writes:

We had received necessary permission from the Watch Committee, but the Cinematograph Exhibitors’ Association feared competition from these new ‘Film Societies’ (as they still do) and went into the attack on the grounds that this was the thin edge of the wedge to Sunday opening, which they at that time opposed.

As Baron mentions, there was strong opposition to Sunday screenings in Leeds at that time. Restrictions on Sunday cinema opening had come into place following the Cinematograph Act of 1909. A piece of legislation designed to regulate the safety of cinemas, it also gave local authorities the power to dictate which days a cinema could open, and as a result, many forbade Sunday screenings on moral and religious grounds, upholding the Sunday Observance Act of 1780. Enforcing this legislation were local Watch Committees. These were powerful committees composed of local council, ostensibly set up to oversee the police force, but in practice they administered an eclectic variety of activities, including the granting of cinema licences, and so could act as moral gatekeepers, dictating what films were screened in their district.

Conversely, in this instance the Leeds Film Group had the approval of the local authorities but were instead thwarted by fellow exhibitors. After initially being granted permission by the Watch Committee to hold private Sunday screenings at the Academy, a protest was launched by the local branch of the Cinematograph Exhibitors Association (CEA). Formed in 1912, the CEA was a national organisation that represented the interests of cinema owners. The CEA opposed the screenings for several reasons - they argued that there was not substantial demand for such performances and believed the Group would be using the cinema to show uncensored films, as one of the CEA complained “if uncensored German and Russian films were going to be shown to the members of this organisation, as seemed probable, it was extremely unfair to the ordinary cinematograph licence holder” (Leeds Mercury 02 Dec 1933). In a retort from a ‘Leeds Film Grouper’ in the Leeds Mercury, they wrote:

The Film Group intended to show films which would never be shown in the commercial cinema—not because, as one exhibitor rather stupidly suggested, they are uncensored, but because they are artistic films with a strictly limited appeal. No commercial cinema owner would dare to risk his receipts by showing them (Leeds Mercury, 06 Dec 1933).

As Baron believed, it certainly appeared as though the CEA viewed the Leeds Film Group as competition, as well as misunderstanding it, disapproving of them hosting screenings when other cinemas were closed, regardless of the Group’s private membership.

Despite strong support from the local press, after two successful seasons the Leeds Film Group went on hiatus, but this was by no means the end of their activities and it would constitute the first of many iterations and identities. With the opening of the Academy on Boar Lane, appreciators of art cinema were well catered for and it removed the need for a film society during its years of operation. In those years Baron would turn his attention to supporting the formation of the British Film Institute, establishing a pressure group called the Leeds Film Institute Society. In the next post I will return to the Academy Cinema Leeds, looking in detail at the “Yorkshire Home of unusual and artistic films” and its sister venue in Oxford Street, the first dedicated art cinema in the UK.

References

Leeds Film Group Summer Session 1933 membership card, Alec Baron Archive, BC MS 20c Theatre, Baron/Box 1, University of Leeds Special Collections

Leeds Film Group letter/press release, c. 1933, Alec Baron Archive, BC MS 20c Theatre, Baron/Box 1, University of Leeds Special Collections

Untitled typed document on the history of the Leeds Film Group, Alec Baron Archive, BC MS 20c Theatre, Baron/Box 1, University of Leeds Special Collections

Alec Baron’s unpublished memoir, 1991, Alec Baron Archive, BC MS 20c Theatre, Baron/Box 13, University of Leeds Special Collections

‘The Film Public at Fault’, Yorkshire Evening Post, Saturday 01 July 1933

‘Unusual Films May Pay’, Yorkshire Evening Post, Saturday 29 July 1933

‘Harvest Time of Pictureland’, Yorkshire Evening Post, Saturday 26 August 1933

‘Sunday Cinemas Not Wanted’, Leeds Mercury, Saturday 02 December 1933

‘Sunday Films in Leeds’, Leeds Mercury, Wednesday 06 December 1933