Part 3 - “An International Season of Fine Films” - A History of Leeds Film Society

By Alice Miller

In this blog post, I explore another key group working within independent film exhibition in Leeds and delve into the history of the long-running Leeds Film Society, a voluntary organisation that sustained artistic and cultural cinema in the city for over four decades. The Society operated out of a succession of local cinemas, including two beloved historic cinemas that remain open today.

The years of the Second World War had largely brought a hiatus to amateur film exhibition activity in Leeds, but after the war, interest began to swell for a new film society that would follow in the footsteps of the Leeds Film Group (see previous blog). In 1946 cinema-going in the UK was at an all-time high, with cinema admissions reaching a peak of 1.64 billion. In the years immediately following the war, cinema experienced a boom and this period is widely regarded as the golden age of cinema-going. Post-war was also a time in which the commercial exhibition industry became even more homogenised, as a duopoly emerged in the form of Rank and ABC, two cinema chains who would come to dominate the cinema landscape, controlling over 1100 cinemas between them. With cinema-going the primary pastime of the British public, this was an opportune moment to form a film society, and an alternative to commercial cinema exhibition was needed more than ever.

A public meeting was held on Sunday 20th October 1946 at the City Museum on Park Row to discuss the formation of this new film society, with the aim to establish a group that would show “outstanding examples of the secular feature film made in England, America and on the Continent”. Extra effort was taken to ensure that the meeting and Society were enticing prospects. To provide an example of the types of films they would be programming, Rene Clair’s The Italian Straw Hat (1928) was screened on 16mm, and to give further impetus to the Society’s launch, the Ealing Studios film director Charles Crichton was also present as a special guest speaker, coming straight from the set of his latest film Hue and Cry (1947).

A handout from the initial meeting read “There is a general demand in Leeds for films not usually shown in the commercial cinemas, for example the older classical British and Foreign feature films, documentaries, films historically significant, early actualities, etc. It is felt that this demand can best be satisfied by forming a Film Society.” This text is illustrative of typical film society motivations, a focus on films excluded from commercial cinemas, and makes evident the programming direction of the Society. The new society planned to screen films on 35mm, using the Tatler Cinema on Boar Lane (formerly the Academy Cinema) once a month, with screenings at 10.30 a.m. on Sunday mornings.

The inaugural screening was held at the Tatler Cinema on 17th November 1946 with a showing of Children of the City (a documentary short about child delinquency in Scotland produced by Paul Rotha) and the Orson Welles directed Citizen Kane. Released in 1941, Citizen Kane was already regarded as a screen classic by the Leeds Film Society, “keenly sought by students of cinema”, and it was chosen for the first programme due to the many requests from members. By the first screening, the Society had already recruited 150 members, halfway to its target of 300. Subscription fees were advertised in three tiers, for Patrons, who could reserve seats, £1-1-0 (one pound and one shilling), Ordinary Members 12/6 (12 shillings and 6 pence) and for Student Members 7/6 (7 shillings and 6 pence).

Upon forming, and ahead of its first event, the Society set out a constitution:

The objects of the society shall be: 1. To encourage interest in the film as an art and as a medium of information and education by means of exhibition of films of a scientific, educational, cultural and artistic character. 2. To promote the study and appreciation of films by means of lectures, discussions and exhibitions.

A later revision to the Constitution added a third objective: “3. The Society shall be non-political and non-profit making. Non-political means the Society shall not espouse the cause of any political party.” Commercialism was closely associated with the mainstream film industry, and its profit-driven nature was considered detrimental to the production and exhibition of quality cinema. In remaining staunchly non-profit, film societies were seeking to provide an alternative to mainstream cinema exhibition, not just in their film choices, but through their financial and operational models as well.

Society membership was open to everyone over the age of 16. Members paid a seasonal subscription fee which entitled them to all screenings, lectures, discussions, and other Society meetings. Members could bring guests, if pre-arranged with the committee. This type of membership model was typical of film societies and had been replicated since The Film Society (London) had first established it in the 1920s. Despite the private members-only nature, film societies were ever keen to expand their audiences and attract new members. The model was adopted not to be prohibitive, but to provide vital income with which to cover the expensive costs of running a film show. Opening up screenings to paying non-member guests was also a way to generate further funds to cover the running costs of the Society. The membership model removed the need for an exchange of money to take place at the screenings, thus further distancing the societies from the commercialism of mainstream cinemas. The society was run by a committee of at least six members, including a chairman, two joint secretaries, and a treasurer, and committee members were elected on a yearly basis at the annual AGM. The committee was responsible for selecting the film programmes, setting the membership fees, and deciding on the date and location of film screenings and meetings. All funds made went back into the society, to cover the costs of screenings, meetings, and events, and as a voluntary-run society, no members received payment for their work.

First season at the Tatler

The Society had a successful first season and had gained 187 members in its initial six months, which was slightly short of their target, but still sufficient to keep it going financially. The need for further members was forcefully stressed in Society newsletters, to ensure they met their educational aims and the high standards set by other societies, and existing members were encouraged to each introduce a new person for the future season. Following Citizen Kane, other films screened in the premiere season included: Quai Des Brumes, All That Money Can Buy, Papageno, Song of Ceylon, The City and A Night at The Opera.

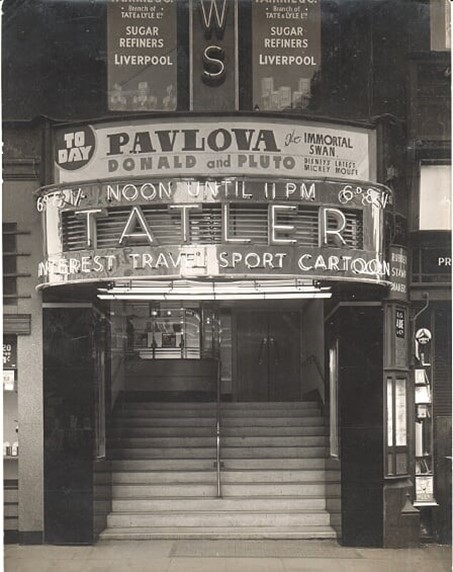

The Tatler Cinema, managed by A.E. Shaverin during this period, was a receptive home for the Society, having formerly been used for the repertory cinema The Academy (see previous blog post). Shaverin was on the Society committee which suggests that despite being a commercial cinema operator, he sympathised with the society’s aims and lines of programming. The cinema during this time was owned by Allied (Times) Cinemas Ltd., who also operated cinemas in Manchester and Chester. In Society newsletters, additional foreign-language films playing at the Tatler would be recommended to the members, as the Tatler operated a repertory policy outside of the Society’s usage. Rather than viewing the Tatler as competition, the society aligned itself with the cinema, adding to its continental programming.

Tatler Cinema, Boar Lane, Leeds

The second season of the Leeds Film Society launched in October 1947 and ran until March of that year, with each feature-length film programmed with an accompanying short. The films included Lermontov paired with Felix Wins and Loses, The Blue Angel with Harold Llyod short The Chef, The Grapes of Wrath with Chaplin’s first films, Hotel du Nord with The Line to Tschierva Hut, Ils étaient neuf célibataires with The Seashell and the Clergyman, and Western Approaches with North East Corner. Coinciding with the launch of their new season, the Film Society arranged a course of lectures on the "Appreciation of Film," given at Swarthmore Education Centre, each Friday evening until Christmas. These lectures furthered the educational mission of the film society movement by providing informal education to members of the public. Founded in 1909, Swarthmore was a leading centre of adult education in Leeds and remains so today. Such courses were indicative of the strong link between the film society movement and adult education, as well as the key film society objective of furthering film appreciation through informal education strategies.

Later in October 1947, the Earl of Harewood, George Lascelles, became president of the Society. The Earl was a keen supporter of the arts, particularly music and opera, and would go on to become the director of the English National Opera. Later in his career, he would assume another leadership role in film, becoming the president of the British Board of Film Classification in 1985. The 1946 reformation had marked a shift in the demographic of Society leadership. Its predecessor, the Leeds Film Group, was steered by schoolboys from low-income families. Now spearheaded by the Earl, the Society had a distinctly middle- and upper-class make-up. Committee members were also embedded in the cultural life of the city, with many having influential careers. Over the years, Committee members included: Society Secretary Ernest Bradbury, a long-running music critic for the Yorkshire Post; Society Chairman Ernest Musgrave, the first Director of Wakefield Art Gallery and subsequently Director of Leeds Art Gallery; Society Treasurer Beryl Davies, founder and former Headmistress of the private school Richmond House in far Headingley (formerly Miss Davies School); and Society Secretary Alan Weir, a film critic for the Yorkshire Evening News.

In October 1949 an open meeting was held to discuss the future of the society. A fall in membership had prompted the group to discuss its future and it was hoped the meeting would encourage an increase in members so that they could proceed with a winter season. The Society divided their next season into three sessions, January-March, April-June, and October-December, and launched with a screening of John Ford’s The Long Journey Home in December 1949. The season included a mix of screenings held at the Tatler on 35mm and 16mm showings at the City Museum. Films included Strange Incident with the Dragon of Krakow, Madchen In Uniform, Voyage Through the Impossible, The Passion of Joan of Arc with They Travel by Air, Duck Soup and La Naissance du Cinema.

1950s

Following the peak of cinema-going in 1946, the 1950s saw cinema audiences begin to steadily diminish and the closure of cinemas. The advent of television was one factor blamed for audience decline, with it having a substantial impact on cinema admissions from the mid-50s onwards, as more families could afford TV sets. Another factor affecting cinema exhibition in this decade were major changes in the American film industry. In 1948 the Paramount Degrees came into effect, separating film production from exhibition and making it illegal for film studios to own their own cinemas, thus bringing an end to vertical integration of the Hollywood studio system. Although this change in law was beneficial for the independent sector, and led to a rise in independent cinemas, the collapse of the studio system had a knock-on effect on film production, and resulted in fewer studio films made available for US and UK commercial cinemas.

While commercial cinemas suffered in this decade, film society memberships continued to grow. However, societies were not entirely safe from threat as an increasing number of commercial cinemas began taking chances with foreign-language films. With a shortage of quality British and American films to service second and third-run cinemas, smaller-sized and suburban cinemas turned to the showing of international films, particularly to those from France, and with box office profits proving just as healthy as those for British and American fare. However, they remained in the minority, as the high cost of dubbing meant that money could only be recouped via a wide release. Indeed, Leeds Film Society was not the only place to see foreign-language cinema in this period. A newspaper article reported in July 1950 “Those who like occasionally to see what the French cinema is producing are no longer limited to the few city cinemas which courageously specialise in foreign films, or to private Sunday showings such as the Leeds Film Society have provided. At least two suburban cinemas in Leeds, for example, are giving three-day runs to French films once a month on average” (Yorkshire Post July 7, 1950).

Headingley Picture House

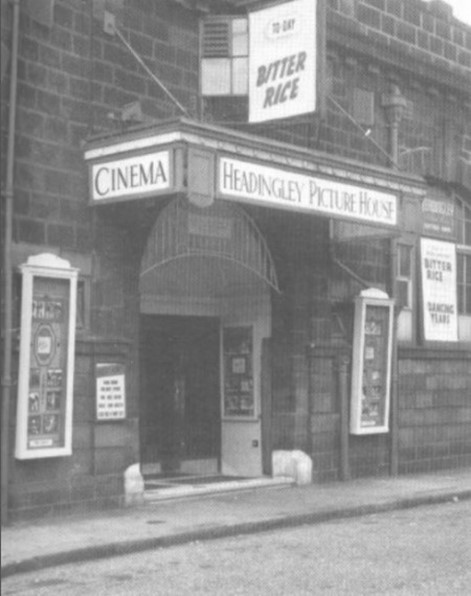

Headingley Picture House (now Cottage Road Cinema), Cottage Road, Leeds

The Society remained at the Tatler until the summer of 1950. For their 1950 winter season the Society moved to the suburbs for the first time, using the Headingley Picture House on Cottage Road. The Headingley Picture House had opened in 1912, making it one of the oldest cinemas in Leeds. Owned by the Leeds-based Associated Tower Cinemas, the cinema was described by former manager John R. Broadley as “a small, comfortable, intimate suburban cinema”. The cinema seated 590, which was considered a modest number at the time, and was frequented by patrons from the local area. Broadley, who became manager in 1951, recalls a loyal audience that would return week after week, often sitting in their same favoured seats. This dedicated and returning audience resulted in a sociable and homely atmosphere, where staff and patrons where on first name terms, and it made for a more intimate and friendly experience than at the larger city centre cinemas.

Screenings switched from Sunday mornings to Sunday evenings at 7pm. Seasons continued to be programmed in blocks of six screenings, running from October to March, with the cost of the six-film season increasing to 15s, and each feature programmed with an accompanying short or a selection of shorts. The venue change paid off as this inaugural season in Headingley was to be the Society’s most successful yet. The programme predominantly contained French titles, along with Swedish, US, and Italian-French co-produced films. One notable title was Hets directed by Alf Sjöberg from a script by a young Ingmar Bergman early in his career, a film now regarded as a key work of Swedish cinema. Other films in the programme included Jean Cocteau’s poetic fantasy La Belle et la Bete, the French musical comedy Le Million directed by Rene Clair, French historical drama Monsieur Vincent, and Roberto Rossellini's Germany Year Zero. The season had made £80 profit and by September of 1951, the Society membership had grown to 321, finally reaching a desired number that would make the Society sustainable and financially stable going forwards. The previous year membership had worryingly dropped to 90 and the Society had operated at a deficit. The low membership numbers in 1950 go some way to explaining the change in Society venue, as it was perhaps felt that a shake-up was needed. Moving to suburbs brought the Society into closer orbit with their middle-class members, as Headingley was an area where some of the more affluent inhabitants of Leeds lived. Venue capacity was also likely a factor, as since its conversion from the Academy cinema in 1936, the Tatler could only seat 299, and so would hinder any Society growth beyond this number.

Hosting the society was quite an honour for the Headingley-based cinema, and the society brought a new and prestigious clientele with them. It was widely reported in local newspapers that Earl of Harewood and Lady Harewood attended the opening film of the 1951 winter season, and joining them was the politician Hugh Gaitskell, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and MP for South Leeds at that time. Headingley Cinema manager Broadley remembers the evening as “an occasion which I will never forget”. This season was launched with a screening of De Pokkers Unger, a Danish film from 1947 co-directed by husband-and-wife duo, and pioneers of children’s cinema, Astrid and Bjarne Henning-Jensen.

The programmes from the 1950s show a strong leaning towards French cinema, and with only a few silent films, the Society favoured relatively recent films made within the previous ten years. This was common in the programming of 35mm societies, who had greater access to recent releases available on that film format and could programme 35mm films following their circulation in London cinemas. This was in contrast to 16mm film societies, who tended to show a greater number of silent films due to what was available on the small gauge film format.

The 1954/55 season brochure acknowledged a rise in the standard of film appreciation, with more of the “better” films being released in commercial cinemas, thus narrowing the field for film societies. The rise in commercial exhibition of foreign-language cinema in the 1950s continued to pose a real concern for societies. In 1956 the Kinematograph Weekly published an article on the growing influence of continental film, noting that French and Italian film had particularly caught hold of UK audiences. Statistics included in the article showed that in 1951 320 cinemas outside of London were screening French films, and by 1955 this number had risen to 1200 cinemas. The film society movement was considered to be a victim of its own success, helping to foster an appreciation of cultural cinema, only to have commercial cinemas take over the mantle. The Leeds Society met this existential threat head on, announcing “this season has taken the bold step of offering a new show each fortnight: it does so with confidence”. Screenings doubled to 12 per season and the cost rose to one guinea, indicating conviction in the continued success of the Society and a strategy to increase opportunities to see artistic cinema. Such an approach appears to capitalise on the increased exposure and popularity continental films were getting via the commercial cinemas. This expanded programme comprised features from France and the US, with a diverse array of shorts.

The Lyceum

Lyceum Cinema, Cardigan Road, Leeds

In October 1958, after seven years at the Headingley Cinema the society moved once again, this time to the Lyceum Cinema on Cardigan Road, remaining in suburbs, but relocating to the Burley area of Leeds. Though moving away from the affluent Headingley, the new location was advantageous to the Society. Residing at the threshold of the Hyde Park and Burley districts, and at a junction near a busy crossroads, the former manager remarked that “the siting of the cinema was ideal for attracting patrons from all directions”. The cinema seated 900, ample room for the Society to continue growing its membership.

The society continued with the format of 6-month seasons of 12 screenings, but now priced at the slightly more expensive 25 shillings. In a critical round up of the Leeds film scene in the Union News student newspaper in 1961, the reporter writes of the Film Society “Its programme this year is good, but to get in means joining the Society and joining the society means twenty-five shillings down”, highlighting the prohibitive cost and exclusivity that came with the film society. The 1959/60 season at the Lyceum included Indian cinema for the first time, showing Pather Panchali directed by Satyajit Ray. The film’s prize-winning Cannes appearance likely brought it to the attention of specialist cinemas and film societies, and the film was distributed by Curzon’s distribution company. The 1961/62 programme included Shoot the Piano Player, the Society’s first foray into French New Wave. The most popular films of that season, in order of popularity, were The Rickshaw Man tied in first place with La Grande Illusion, followed by Roses for the Prosecutor, Summer Interlude, The Captain from Köpenick, The Baker of Valorgue, Shoot the Piano Player, Fric-Frac, Pickpocket, Vie A Deux, Sign of Venus and lastly, Ah! The Beautiful Priestesses of Bacchus. The least popular films being the lighter, and more salacious comedies.

Commercial cinemas experimenting with continental films had continued to provide worrying competition for film societies across the country. In Leeds, the threat was short lived, and the society even bemoaned the loss of other venues to see international cinema. In a letter to the members in 1964, the closing of the Tatler Theatre on Boar Lane, their former home, is remarked upon, with its closing meaning “the opportunities to see foreign films have become few and between.” Despite a loss for the Leeds film scene, this closure also presented the Society with an opportunity to increase its members, filling a gap left by the cinema and continuing to provide a service to film-goers seeking out international cinema. The Society continued to hold the belief that many people in Leeds had film tastes that could be catered for, if only these people knew of its existence.

By the end of 1966/67 season the Society had reached 499 members, which included 54 student members. This season had included the trial of a children’s screening, where members could bring their children free of charge as guests of the Society, though the Society stressed that members without children were also welcome. The Society had also held a ‘Celebrity Film Lecture’, inviting Roger Manvell to speak at Leeds Art Gallery, based on a similar model to the National Film Theatre’s ‘celebrity lectures’. Manvell’s writings on film were influential to the film society movement, particularly his book Film, first published in 1944, which surveyed cinema and provided useful information such as how to start a film society, further reading, and a list of recommended films. Discussion evenings were also introduced by the Society, with the first one held at Bradford Playhouse Theatre with a mix of members from both city’s societies attending. The success of the season prompted the Society to increase screenings to 16, with no extra cost for the members.

The 1967/68 season was the Society’s most successful yet. The Society was inundated with member requests and had to close membership applications early for the first time in their history, turning away 100 prospective members. Members had grown to 606, which included 121 student memberships. Keeping up to date with the latest film trends and movements in cinema, this season also saw the Film Society embrace underground cinema. A screening of underground cinema was held in Leeds Art Gallery in January of 1968, as an addition to the regular Sunday showings at the Lyceum, and was likely instigated by Leslie Reyner who regularly organised screenings of rare and experimental cinema at Swarthmore Adult Education Centre. Highlighting the event, a society newsletter from November 1967 read:

Have you read about the Underground Cinema? This is the name given to a body of way out film-makers who have discarded convention and recognised standards, a movement which has spread rapidly in America, and now to England. The films which vary considerably in style (and quality) have no appeal to commercial bookers and are usually shown in converted basements (hence the name) often to a packed house. Whether this is an aberration of a new trend, cinematic anarchy or true avant-garde remains to be seen.

The tone of the newsletter betrays a hint of scepticism with regard to this emerging cinema. The secretaries' report later reflected on the event, stating that “To everyone’s surprise the turn-up was so great that many were turned away. Whether the films merited this response is another matter”, once again expressing doubt on the value of the films. Nevertheless, the Society’s programming indicates a desire to embrace new and challenging forms of cinema, and give Society members a chance to make up their own minds. The 1968 season would also be the Society’s most diverse in terms of global cinema, with the films An Actor's Revenge (Japan), The House of the Angel (Argentina), The Round up (Hungary), Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (Ukraine), The Childhood of Maxim Gorky (Russia), The Saragossa Manuscript (Poland) as well as titles from France, Italy, West Germany, Sweden and the US. The Society was also engaging with the French New Wave, showing Godard’s A Woman Is a Woman, and Agnes Varda’s Le Bonheur.

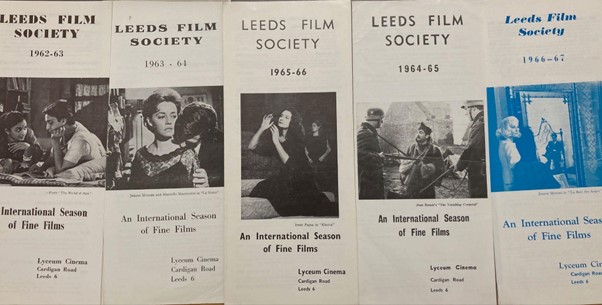

Leeds Film Society programmes 1962 - 67

This successful season came to a close with the news that Lyceum Cinema was converting to Bingo. The Society had final usage of the cinema, showing a selection of Paul Rotha films on the 12th May, with the projectors and equipment being taken down after the screening that evening. With cinemas turning to bingo, the Society was starting to feel the effects of a struggling commercial cinema sector. The industry was in crisis mode. Commercial cinema-going had continued to decline, impacted by changing leisure habits, demographics, and the ever-growing dominance of television. Cinemas fought this decline with diversification, adapting their cinema spaces into dance halls, bowling alleys and bingo. At the start of the decade there were 3819 cinemas in the UK, and by 1969 this number had fallen to 1581.

Hyde Park Picture House

Hyde Park Picture House circa 1970s, Brudenell Road, Leeds

Not to be deterred, the Film Society continued on. After searching for a suitable venue, the Society secured the use of the Hyde Park Picture House, just round the corner from the Lyceum. A suburban picture palace, the Hyde Park had opened in 1914, and by the late 1960s the cinema catered for a growing student population residing in its vicinity, supplying them with repertory screenings of predominantly X rated films from the American New Wave, British Kitchen Sink, sexploitation, and occasional European arthouse.

The Society agreed usage of the cinema every Sunday evening for six months, starting from October 6th, 1968. Hyde Park was not an ideal choice for the Society, as its size meant that it couldn’t accommodate all of the members. In 1968 the Hyde Park had a capacity of 448, compared to the Lyceum’s 760. To reach a solution and accommodate everyone, the Society proposed to organise two film seasons running on alternate Sundays. Each season was open to 350 members, with the remainder of seats made available for guests. For a cost of 30 shillings, members could opt for either Series 1 or Series 2, based on which selection of films they preferred, and they could attend films in the other series for the price of a guest ticket. Members could attend both full Series’ for £3. Due to the doubled quantity of films booked, smaller capacity cinema, and limited number of guest tickets, these seasons were expected to operate at a loss and be subsidised by Society reserves. To the Society’s surprise, the screenings did better than expected, packing out the Hyde Park cinema and making a profit. Despite the success of the dual seasons, it had been a huge undertaking for the Society, changing cinemas once again, arranging a screening every week for six months, and booking a total of 65 films. For the second year, they were inundated with membership applications, and several hundred applications had to be refused and cheques returned.

The committee still felt the Hyde Park was not the most suitable cinema for the Society but were unable to source an alternative that could cater for Sunday evening screenings, and so the Society remained at the Hyde Park for its 1969/70 season. From the perspective of an audience member, the Society screenings were a highlight in the Hyde Park programme. An interview conducted by the staff of Hyde Park with a local regular several years ago contains an illuminating recollection of the film society screenings at the Hyde Park:

The Sunday night film society was absolutely great because the place was packed. People from all over Headingley came. I suppose there were students but there were people who had come as a student, like me, and stayed on. And it was really sad when that finished. I remember why, I think it was something to do with the new Playhouse opening and then setting up a film show on Sunday night, but it was nowhere near the same atmosphere - Hyde Park regular

When the Society first approached Hyde Park, they were already looking into to the possibility of finding a cinema that could function as a new Leeds branch of the National Film Theatre (NFT) as well provide a home for the Film Society, with the idea that the Society would show screenings on alternate Sundays and the Leeds NFT using the other Sundays. This idea was nixed due to the small capacity of the Hyde Park, as priority was given to catering for Society members. The committee continued its search for a venue that could become part of the NFT.

Film Selection

In order to programme each season, the Society committee would consult various resources and sources of research. The most valuable resource was the Annual Viewing Sessions co-organised by the BFI and the British Federation of Film Societies (BFFS), with 4-5 committee members usually attending. Distributors such as Connoisseur, Contemporary, Golden Films, Hunter Films, and Rank Film Library would supply their films. Regional viewing sessions were also organised in Yorkshire. To guarantee the quality of the film, efforts were made to ensure that at least one or two committee members had seen a film before it was booked. The Film Society also worked with the Central Booking Agency (CBA) to book their films, a department within the BFI that acted as a mediator between the film societies and commercial distributors. For a small cost, the CBA would arrange the booking and negotiate the hire terms of a particular film with a distributor, acting on behalf of a film society. The Society committee would attend film festivals, with the main ones being London and Edinburgh, and were also free to book films directly from the renters and distributors, regularly pursuing the printed catalogues sent by distributors listing their new and historical titles. The Society would also look to other film societies, keeping an eye on the programmes of Bradford, Wakefield, and York.

Further useful printed matter came from the Federation. The Federation produced two publications, the quarterly Film News bulletin and the monthly Film magazine. Simple in format, Film News, was invaluable to the Society programmer, containing reviews written by society members of recent and forthcoming releases on 16mm and 35mm, and listing available films by distributor. It also included reviews of films from the latest viewing sessions, film festivals such as London, Edinburgh and Cork, and films showing at specialist London cinemas. The magazine Film, was aimed at a wider audience, containing reviews by a mix of amateur and professional critics, and featuring longer articles on issues affecting the societies and film culture at large. Copies of Film were sold at Leeds Film Society screenings at a reduced price for members.

The Society also turned to its audience to guide the programme. Taking a democratic approach that involved all Society members, the Film Society committee would draw up an extensive list of film titles available to book for the forthcoming season, and members would be invited to vote on these films, putting a tick next to their twelve top choices. Members were also asked at the end of a season to rank the films screened in order of preference. At each Society screening audiences would be asked to rate the film at the end via a voting slip, marking it A very good, B good, C fair and D poor. This would then help the committee with the selection of future programmes, giving them a sense of audience likes and dislikes.

Programming

The 1940s and 50s programmes of the Leeds Film Society displayed eclectic, wide-ranging and distinctive selections. Early experimental cinema was represented with titles such as The Seashell and the Clergyman, Entr’acte, the shorts of Norman Mclaren, Lotte Reiniger silhouette animations, and Robert Florey’s Life and Death of a Hollywood Extra. All seasons included a number of comedies, typically in the form of a Harold Lloyd, Chaplin, Keaton or Marx Brothers film. The programmes highlight that the Society sought to give their members a well-rounded experience, showcasing film in all its diversity and not just staying within the confines of the established film canon. The Society programmes catered for a mix of tastes and demonstrated good balance, juxtaposing different forms of cinema, as well as a mix of tones, periods, and countries. The accompanying shorts brought further variety to the programmes, adding an eclectic and pluralist mix of scientific films, experimental animation, cartoons, comedy, newsreels, serials, and documentaries. This type of mixed, contrasting and multifaceted programming was prevalent in the 1940s and 50s, and can be seen as following on from the early programmes of The Film Society in London which established this type of programming in the 1920s and 30s.

Leeds Film Theatre

In 1970, the Society was finally able to realise its ambition to establish an art cinema, using the new Leeds Playhouse as its base. In 1966, the BFI had initiated a scheme to establish a chain of Regional Film Theatres (RFTs) modelled on the National Film Theatre, setting up full-time RFTs in Brighton, Manchester and Newcastle, as well as several part-time ones. Taking advantage of this scheme, the Society was able to set up a part-time Regional Film Theatre in Leeds. Run and programmed by the Society, the Leeds Film Theatre launched in September of 1970 and this next period in the life of the Film Society and Film Theatre will be looked at in the next blog post.

The Leeds Film Society displayed a tenacity and determination to circulate and support film as an art form, and they remained dedicated to the film culture of Leeds. With the city lacking a permanent arthouse cinema, it was a voluntary organisation that sustained artistic and cultural cinema in the city for four decades, operating at the margins of the commercial mainstream, and in close partnership with commercial cinemas and cultural venues. A consistent presence in the cultural landscape, the Society carved out a space for art cinema, nourishing the film culture of Leeds and the region. Their endurance, diversity of programme and ethos, paved the way for the internationalist Leeds Film Festival, the independent and community-focused Hyde Park Picture House, and the DIY film culture that exists today. Through democratic organising and active participation, the Leeds Film Society cultivated loyal audiences, and developed tastes for cultural cinema. Without their sustained activities, and a continued cultivation of art audiences, the current landscape of cultural film exhibition in the city would look very different.

References

Anon. 1948. Yorkshire Post 24 April.

Anon. 1949. Yorkshire Post 8 Jan.

Anon. 1950. Yorkshire Post 7 July.

Anon. The Cinema - Theirs and Ours, in Union News. October 13 1961

Baron, A. 1991. unpublished memoir. Alec Baron Archive, BC MS 20c Theatre, Baron/Box 13, University of Leeds Special Collections

Betts, E. 1973. Film Business: History of the British Cinema, 1896-1971. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin.

Bradford, E. 2012. Cottage Road Cinema 1912 - 2012. Web. 19 Jan 2023.

<http://btckstorage.blob.core.windows.net › site3746>

Broadley, J.R. 1990. Facing the Fifties: A Life in Leeds Cinemas. Picture House. 14. 31-38.

Hanson, S. 2007. From silent screen to multi-screen : a history of cinema exhibition in Britain since 1896. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Harper, S & Porter, V. 2003. British cinema in the 1950s: the decline of deference. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Leeds Film Society. 1947 - 1989. Leeds Film Society and Leeds Film Theatre programmes. Alec Baron Archive. Special Collections, University of Leeds.

MacDonald, R.L. 2019. The appreciation of film : the post-war film society movement and film culture in Britain. Exeter: University of Exeter Press.

Manning, S. 2020. Cinemas and Cinema-Going in the United Kingdom: Decades of Decline,

1945–65. London: University of London Press.

Mazdon, L. and Wheatley, C. 2013. French film in Britain : sex, art and cinephilia. New York: Berghahn Books.

Nowell-Smith, G. and Dupin, C. (eds.) The British Film Institute: The Government and Film Culture 1933-2000. Manchester: Manchester University Press.