Part 2 - “Purely a shelter for art”: How Leeds became home to the first repertory cinema in the provinces

By Alice Miller

In the second post in this series, I explore another important moment in the history of independent film culture in Leeds by taking a deeper look at the Academy Cinema on Boar Lane, regarded as the first repertory cinema in the provinces. In this post, I will consider how the cinema came about, its years of operation, changing identities, and what brought it to an end. The venue was used as a testing ground for expanding and introducing repertory cinemas outside of London. The term ‘repertory’ was commonly used to denote a type of cinema that specialised in art and foreign-language films, including new and historical ones, offering wider choice than a mainstream cinema.

In 1933 the city’s first film society, the Leeds Film Group (see the previous blog post), had taken on the lease of a local cinema on Boar Lane, the Savoy, with the aim of hosting a season of screenings. When the season fell through, the Group brokered an association with the manager of a London repertory cinema, the Academy Cinema on Oxford Road. Leeds Film Group founder member, Alec Baron recalled: “the Savoy was reopened as the Leeds Academy Cinema in September 1933 as the first provincial repertory cinema, showing the films we wanted to show, but now open to the public!” Baron remarked that the Academy ran successfully for many years and so a Leeds film society was not needed during that period. Before I take a closer look at the Academy, I want to revisit its earlier identity, as the Savoy.

Savoy Repertory: The first silent repertory cinema in Leeds

The Academy Leeds may have been the first sound repertory cinema outside of London, but before it became the Academy, the venue had already established an association with artistic and Continental programming (the term Continental was typically used in this period to indicate the programming of films from mainland Europe and is synonymous with repertory, specialised and arthouse cinemas). Four years previously, the Academy had operated as a silent cinema under the name ‘Savoy Repertory’ and was associated with another preeminent London art cinema, the Avenue Pavilion on Shaftesbury Avenue run by Stuart Davis. Run in conjunction with the Avenue Pavilion, Davis agreed to supervise the Savoy, selecting the films and helping with the advertising.

The Savoy Repertory launched on 21st January 1929, with a screening of The Last Moment, an American-made silent film directed by the Hungarian Paul Fejos (a film that was regarded as a masterpiece at the time but is now sadly lost). Ahead of its launch, the 17th January edition of the Yorkshire Post remarked on the Savoy’s opening under the heading ‘The Gloomy Screen’. A journalist known simply as ‘Northerner’ wrote:

This afternoon I talked to a man whom I have long thought to be a myth. He was the intelligent cinema-goer; and he was very enthusiastic about the opening next Monday of the Savoy Cinema in Leeds—the third repertory cinema in the country—and he believes that the venture will be a success. I hope so. The Savoy is not a large hall and there should be enough people who care for the films as an art to fill it regularly week by week. “The Last Moment,” which is the opening film, shows, without any subtitles, the story of a man’s life as it passes through his mind the moment before his suicide. Other films, mostly tragic, are to follow. Still, not all the films will be gloomy. I am glad of this (YP 17 Jan 1929).

Repertory cinemas were aimed at a new kind of film-goer, the ‘discerning viewer’ who appreciated the artistic merits of film and welcomed an alternative to “the usual entertainment offered at the average picturehouse” (YP 21 January 1929). These audiences tended to be middle-class and educated. A Leeds Mercury article by journalist Joyce Mather covering the opening event at the Savoy gives a good sense of the audience demographic: “Every branch of society, literary, musical, professional, medical, was represented. Members of the Leeds Art Theatre, the Leeds Civic Playhouse, and many of the local dramatic societies were there, as well as a host of people interested in the movement” (Leeds Mercury 22 Jan 1929). Some of the illustrious attendees included the Vice-Chancellor of Leeds University James Baillie, socialite Dorothy Una Ratcliffe, and Charles Harold Tetley of the famous brewery family. According to Stuart Davis, there were three different types of repertory cinema audience: “The intelligentsia, the intellectual amateur who likes to follow new art movements, and the ordinary, average middle-class businessman who doesn't go to the cinema as a rule because he does not like the fare provided for “the masses””.

Echoing the mission and ethos of the Leeds Film Group, the Savoy Repertory presented international and art films overlooked by the commercial cinemas, yet unlike the Film Group, the cinema was run as a commercial enterprise, hoping to capitalise on a niche market and find a profitable use for a smaller sized cinema. The Savoy in Leeds formed part of an attempt to create a small chain of repertory cinemas that Davis hoped would spread across the country.

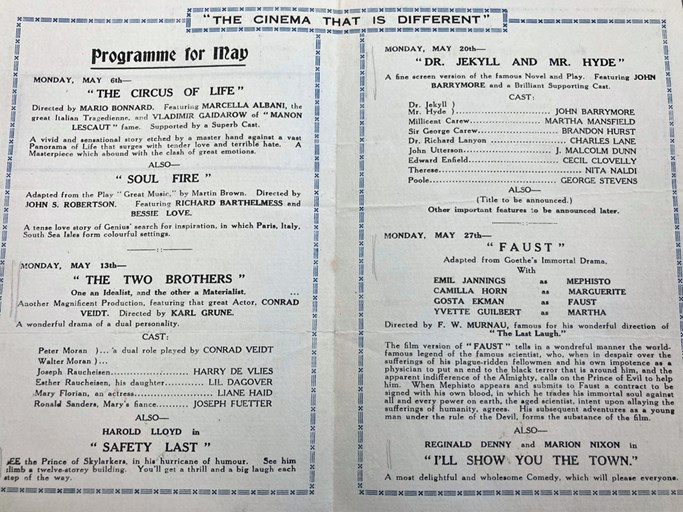

The Savoy’s ambitions are shown in its advertising brochures, which stressed its uniqueness, declaring it as “The Cinema That is Different”, “The Cinema That is Select” and “The Home of Unusual Films”. Showing revivals of silent films, each main feature was accompanied by a supporting feature, usually a comedy. Some highlights from the Savoy programmes included: F.W. Murnau’s Tartuffe and Faust, The Street directed by Karl Grune, Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen, the Harold Lloyd comedies Safety Last and Girl Shy, Buster Keaton’s The General, the Robert Weine directed The Hands of Orlac starring Conrad Veidt and the Ernst Lubitsch directed Forbidden Paradise with Pola Negri.

Savoy Repertory programme May 1929 (Alec Baron Archive, University of Leeds Special Collections)

The Savoy Repertory operated until the end of September 1929, coming to an end after just eight months. In a Yorkshire Post article from 1st October titled ‘The End of the Repertory Cinema’, the reporter lamented the loss of the “bold enterprise” and pondered that it was perhaps inevitable, believing that cinema was too young a medium for repertory and with too few good films to sustain it.

In another Yorkshire Post article from 8th October, the film correspondent spoke with Stuart Davis about some of the reasons for the abandonment of the repertory policy in Leeds. The main problem cited was that the smaller audience in Leeds required a faster turnaround of films, needing a new film after a week or a few days, whereas the London venue had an audience large enough to sustain a film for several weeks, which kept costs down. The Leeds venue, therefore, required additional films to satisfy its audience and could not simply adopt the Avenue Pavilion programme verbatim. This led to increased expenses as well as a shortage of “suitable films of first-rate quality” (YP 8 Oct 1929). Repertory screenings were already a costly undertaking as the films had to be specially imported and often re-edited with English intertitles. The correspondent concluded that the Savoy: “must create a public of its own, as the Avenue Pavilion has done in London. Naturally, this is much harder to do in a smaller provincial city, and, apparently, the rather specialised public required by repertory is not at present to be found in sufficient numbers in the Leeds district” (YP 8 Oct 1929).

Attempting to reignite the repertory cinema movement four years later, the Leeds Film Group would argue that this “specialised public” was present in Leeds but merely dormant. Quoted in the YEP in July 1933, they claimed that: “Aesthetic appreciation of the cinema [...] is by no means entirely absent in Leeds: it is merely latent: and the reason for the failure of the Savoy Repertory was not due to any lack of public support, but the difficulty of procuring suitable films” (YEP 1 July 1933).

Academy Cinema Oxford Street

When London’s Avenue Pavilion ceased its repertory policy, a successor was found in the Academy Cinema on Oxford Street, which came to be regarded as the first permanent arthouse cinema in Britain. The location at 165 Oxford Street had been associated with film exhibition as early as 1906, when it was a venue of Hale’s Tours of the World, an American franchise and attraction that simulated a train ride, with audiences viewing travel films projected onto a screen within a train carriage, augmented with sound effects and movement. In 1913 the venue became the Picture House cinema, renamed the Academy in 1928, and changed its programming direction in 1931 with a series of Continental films spearheaded by Elsie Cohen. Cohen was a pioneering film programmer whose work and influence would reach beyond the capital and soon be seen on the screens of Leeds.

Elsie Cohen

The Dutch-born Cohen had arrived at cinema programming after working in several other roles in the film industry. After studying at Queens College, London, Cohen worked as a film journalist, becoming Associate Editor for the Kinematograph Weekly. She then worked for a Dutch film company Hollandia, responsible for selling films to the American market, before spending time at UFA in Berlin. Cohen’s work in the Netherlands and Germany had brought her in contact with many new and notable works of cinema and she became determined to bring these European discoveries to English audiences. In an interview from 1971 Cohen recalled:

I was very interested in good films, and I continually saw magnificent films on the Continent that were never seen by anyone in England. And I used to come home and talk to people about them, and say what wonderful films they were making in Europe, and they always said, “Why can’t we see them?” And so I felt this was a job that really needed doing.

Prior to programming the Academy, Cohen had curated a season of films at the Palais de Luxe in Soho in 1930 (shortly after the Avenue Pavilion ceased its repertory programming). Cohen’s friends had purchased the venue and she was given short-term use of the cinema before it was to be converted into a small theatre (it re-opened as the Windmill Theatre in June 1931). Cohen mounted a successful six-month season of international silent classics, including The Last Laugh, Faust, Metropolis, The Gold Rush, Turksib and Steamboat Bill Jr. When that season came to an end, she searched for a new venue to continue her programming work and eventually approached the Academy Cinema, proposing something similar to the Palais de Luxe season. Upon securing the support of the cinema’s managing director Eric Hakim, Cohen launched the Academy’s new programming policy in June 1931 with a screening of the Soviet film Earth, directed by Aleksandr Dovzhenko. Hakim had been a violinist, working in the theatres of the aforementioned Davis family, a musical director and film producer, before finding himself in charge of Academy due to family connections (Hakim was responsible for the Electric Theatres (1908) Ltd. chain of cinemas, of which the Academy was part of). Hakim was amenable to trying out a policy of art and international films, as he had already experimented with a season of French films earlier in the year. Cohen remembers that Hakim “knew nothing whatsoever about foreign films, but thought it sounded like a good idea, particularly the fact that it had been so successful in Windmill Street” (The Silent Picture Summer-Autumn 1971).

The Academy Cinema, Oxford Street, London, 1945

In just a few short years, Cohen had established a dedicated audience for continental films at the Academy. Writing in Close Up magazine in 1933, two years after Cohen joined the cinema, Elizabeth Coxhead pronounced:

Everyone knows the Academy Cinema. When we say Academy, it is as often as not (and how shocked our grandfathers would be to hear it) that one we mean. It is more than a cinema: it is a policy, a promise, a guarantee. Something one has in common with other people, a topic of conversation, a means of making friends (Close Up June 1933).

After programming revivals of great silent films at the Academy throughout 1931, Cohen switched to the screening of new ‘talking films’, holding lavish premieres and weekly press screenings. Cohen would travel to Europe to research and secure the booking of new films that were not being shown in England, acting as a distributor as well as exhibitor. The Academy showed subtitled versions of the international films Cohen sourced, with subtitles frequently provided by Josephine Harvey, secretary of The Film Society (London), of which Cohen was a member. Some of the Academy’s successful films included: Kameradschaft, Mädchen in Uniform, Maskerade, and then later on the films of Rene Clair and Jean Renoir. Cohen also briefly programmed the Cinema House, another cinema owned by Hakim.

Academy Cinema Oxford Street flyer (Alec Baron Archive, University of Leeds Special Collections)

Cohen brought new approaches to cinema publicity, such as the use of a mailing list to share detailed programme information with subscribers at home and abroad. Coxhead writes of the Academy’s “co-operative spirit”, fostered in part by this mailing list and the ensuing dialogue it opened up with audiences, who wrote to the cinema with suggestions - “Gradually the Academy became a nucleus of intelligent film thought, a meeting-ground and a clearing house for ideas” (Close Up June 1933).

To make the cinema accessible, the Academy kept several cinema rows at cheap prices, whilst also catering for upper-class clientele (regularly hosting royalty and laying on champagne buffets). Students formed another key part of the Academy audience, as noted by Cohen: “The greatest interest is taken by language teachers in these foreign dialogue films and groups of students visit the Academy in parties, special terms being arranged on such occasions” (Sight and Sound Winter 1932/33).

Expanding the cinema’s reach, the Academy developed relationships beyond the capital with regional film societies, although Coxhead painted a rather unflattering picture of these local enthusiasts:

Miss Cohen is at present acting as a quite unpaid agent and source of supply to these rather bewildered amateurs; she passes on to them her films, supplies them with endless information and advice regarding the securing of films, and listens with amazing patience to all their long and often unreasonable demands (Close Up June 1933).

Despite being “bewildered amateurs”, the film societies represented a valuable network of film appreciation that was laying the groundwork “for a chain of Academies in every big town” (Close Up June 1933). This goal for expansion would eventually be realised in Leeds.

Academy Cinema Boar Lane: ‘Yorkshire Home of Unusual and Artistic Films’

It was the Academy’s managing director Eric Hakim that led on a regional scheme to expand the Academy and once again, Leeds was chosen as a city to try out the expansion of repertory programming (potentially targeted because of its previous association with Stuart Davis and the Avenue Pavilion).

In July 1933, the Leeds Film Group had publicly announced their aspirations to “work in harmonious connection with the Academy Cinema, Oxford Street” in the Yorkshire Evening Post. A few months later that aspiration would seemingly become reality. Alec Baron of the Leeds Film Group recollected how the partnership came about and claims an integral role in brokering it. Upon hearing that the Academy’s managing director Eric Hakim wished to open a regional repertory cinema, Baron wrote to offer him the lease to the Savoy on Boar Lane (the Group had taken on the lease to the Savoy with plans to host a season of silent films). Hakim and an associate came to meet the boys of the Leeds Film Group, a meeting that Baron recalled decades later:

The two high-powered businessmen who came were astonished to meet two schoolboys with their school caps in their hands. We were treated to a cream tea and then, having inspected the cinema, they asked how much we wanted for the lease. Our reply was that they could have it for nothing if they would open a Repertory Cinema in Leeds similar to the London Academy.

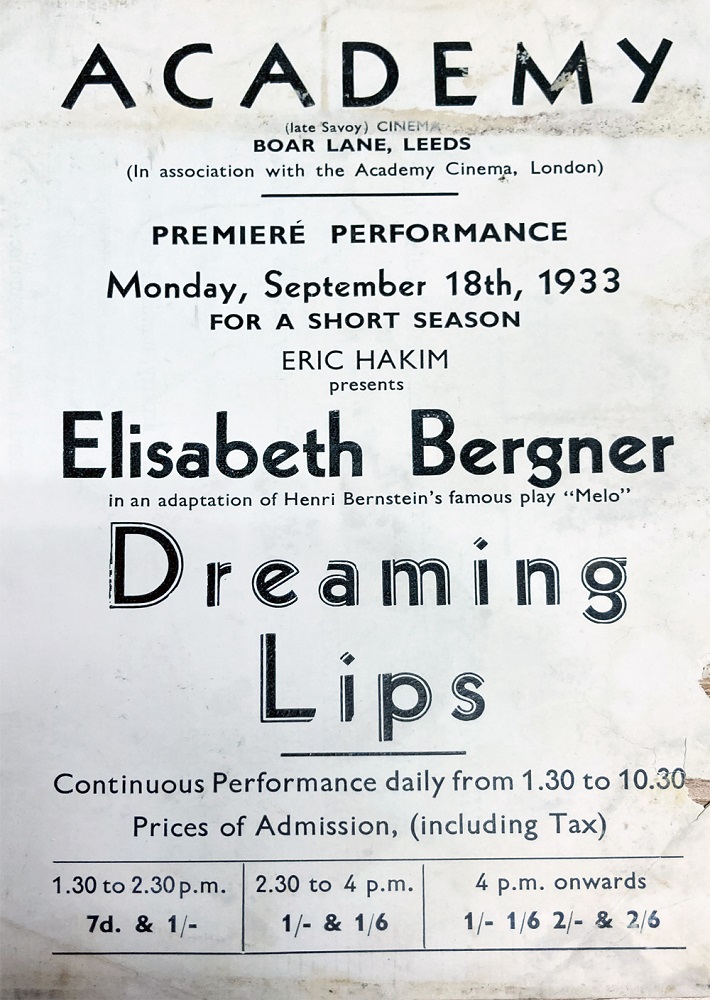

Hakim did indeed take over the cinema and the Academy Cinema on Boar Lane was launched on 18th September with a screening of the French-German co-production Der träumende Mund (Dreaming Lips), with the star Elisabeth Bergner in attendance and a press lunch at the Queens Hotel. Thus Leeds became home to the first provincial branch of the Academy, as announced by the promotional brochure for the premiere performance of Dreaming Lips: “Leeds will be the first provincial town to have its own art film theatre in the manner of the world capitals of London, Paris, Berlin and New York, where the movement has flourished and grown apace.”

Academy Cinema Boar Lane flyer for Dreaming Lips (Alec Baron Archive, University of Leeds Special Collections)

A Yorkshire Evening Post article from 4th September announcing Hakim’s provincial experiment doesn’t mention the Leeds Film Group partnership, but it does pose another reason for Hakim’s selection of Leeds:

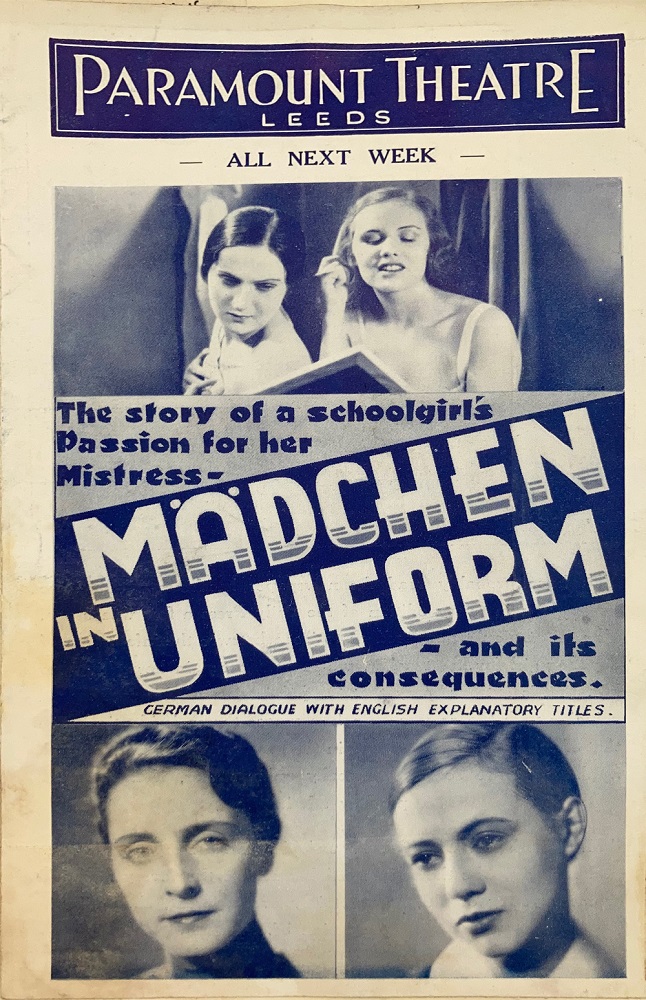

He has chosen Leeds as the first city outside London in which to test his scheme, and hopes to follow it with a chain of such halls. One of the bases of his hopes of success in Leeds is the financial success of "Mädchen in Uniform" at the Paramount Cinema, Leeds, some months ago (YEP 4 Sept 1933).

Paramount Theatre Leeds flyer for Mädchen in Uniform (Alec Baron Archive, University of Leeds Special Collections)

With the local success of Mädchen in Uniform (1931), Leeds had proved itself a hospitable location for the showing of ‘unusual and artistic’ films. A reported 25,000 Leeds cinema-goers viewed the film at the Paramount over a period of six days. Now regarded as a landmark of queer cinema, Mädchen in Uniform is set in an all-girls boarding school and depicts a girl who develops romantic feelings for her teacher. The film was directed by Leontine Sagan and featured an all-female cast. One Leeds reviewer wrote: “I knew Madchen in Uniform was a very good film. I knew it dealt boldly and yet discreetly with one of the problems of adolescence. But no one had told me what to my mind makes its chief claim to distinction, the intense freshness of the acting” (Leeds Mercury 17 Nov 1932).

As with the Savoy, the local press once again welcomed the arrival of a repertory cinema and encouraged its support:

It appears there is a growing public with a taste for the more thought-provoking type of film, because, though business was rather quiet on the Monday and Tuesday, things improved during the latter part of the week. [...] Yes, the serious students of the screen in Yorkshire must rally round and endeavour to keep one little cinema in the county open for the presentation of unusual films (YEP 23 Sept 1933).

The national trade press also covered the new venture, with Cinema Quarterly, under the heading ‘Provincial Repertory’ announcing that “Leeds is the first provincial town in Great Britain to have an art film theatre” (Cinema Quarterly Autumn 1933).

The Academy Cinema, Boar Lane, Leeds (Cinema Theatre Association Archive)

Making the artistic programming policy explicit, Hakim described the Leeds Academy as “purely a shelter for art” (YEP 13 Sept 1933). Although Elsie Cohen was not mentioned in relation to the Leeds venue, her programming was undoubtedly carried over to the Boar Lane cinema. Many titles Cohen programmed in the London venues came to Leeds. Films would first play the Academy, Oxford Street or Cinema House, and then travel up to Leeds for their “Exclusive Provincial Premiere”. Like the London Academy, films ran for one week, with daily screenings taking place from 1.30pm to 10.30pm and prices ranging from 7d. (seven pence) to 2/6 (two shillings and sixpence). It was hoped that the Leeds venue would form the first part of a small chain of specialised cinemas, building on the work done by Cohen in the London cinemas. Hakim had his sights on Manchester and Birmingham as other potential cities to expand into.

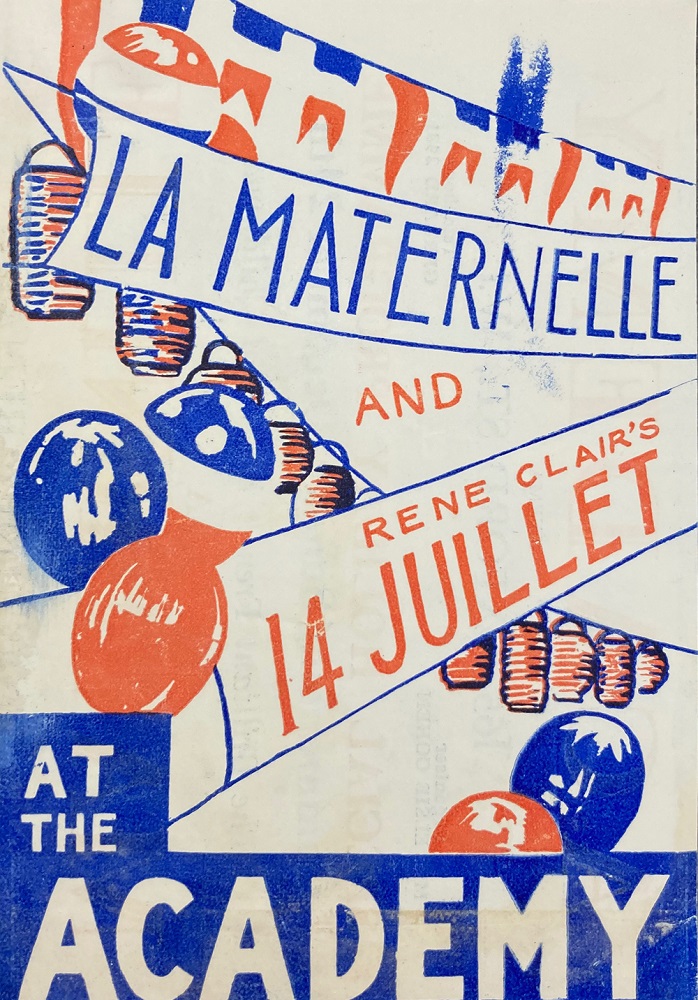

Some of the films screened at the Academy Cinema Boar Lane included Rasputin starring Conrad Veidt, The Tempest starring Emil Jannings, 14th July and Sous Les Toits de Paris directed by Rene Clair, Thunder Over Mexico by Sergei Eisenstein, The Blue Light directed by Leni Riefenstahl, Kameradschaft directed by G.W. Pabst, The Blue Angel starring Marlene Dietrich, and Ernst Lubitsch’s Trouble in Paradise. An article in The Era reported on the language learning benefits of Hakim’s foreign-language programming: “In Leeds, our correspondent writes, quite a few regular patrons to the Academy find in these films excellent instruction in the pronunciation of the French language. Not every student is fortunate enough to be able to take a trip to the Continent in order to polish his languages, but by visiting the Academy he is able to receive both instruction and entertainment at a reasonable cost” (The Era 14 Feb 1934).

On one notable occasion, the Leeds Academy was given a rare film premiere ahead of its London counterpart. On 25 December 1933, Leeds held the UK premiere of the controversial German film Morgenrot, a UFA-produced film set aboard a German U-boat during WW1. The patriotic naval war film was released in Germany just days after Hitler came to power and therefore became the first film released under the Nazi regime. The London branch of the Cinema Exhibitors’ Association objected to screenings of the film and its release in London was postponed. Despite the Leeds Academy showing of Morgenrot, the rise of fascism in Germany ultimately forced Hakim (and Cohen) to look elsewhere for a supply of films, and the main area of focus became the film studios of Paris.

The end of the Academy Leeds

Signs that Eric Hakim’s art cinema ambitions were in jeopardy began to appear in late 1933. A Times notice from November 4th 1933, announced that Hakim had resigned from his role as managing director of Electric Theatres Ltd., Cinema House Ltd. and all of his other companies. Hakim was therefore no longer the managing director of the Academy Cinema London. Conversely, on the same day, the Yorkshire Evening Post reported on Hakim’s work in positive terms: “the support of serious screen students has made Mr. Eric Hakim hopeful with his venture with unusual films—his first experiment in the provinces” (YEP 04 Nov 1933). A few days later, news articles in the Kinematograph Weekly and The Era clarified that Hakim had stepped down as managing director “in order to extend his general activities, which will include plans for a continuation of his programmes of Continental films in the West End and an expansion of same in the provinces” (Kinematograph Weekly 9 Nov 1933) and it was asserted that Hakim would continue to supervise a chain of cinemas. In the Winter 1933-34 edition of Cinema Quarterly, an announcement confirmed that Hakim was no longer involved in Academy Cinema London, but that Elsie Cohen would take over as director.

Despite leaving the Academy London, Hakim continued with his provincial ventures. Around this time it was announced that Hakim had partnered with Ralph Bromhead of the Regent Circuit to extend his continental policy to one of Bromhead’s cinemas, the Prince of Wales Cinema in Liverpool. The Liverpool venue joined Leeds to become the second in Hakim’s provincial chain and launched on 12th February 1934 with a policy of “artistic and ‘uncommercial’ films” (Daily Herald 12 Feb). It was reported that Hakim would select the films for the Liverpool cinema and it opened with a screening of Eisenstein’s Thunder Over Mexico, followed by Dreaming Lips, both of which had played in Leeds a few months previously.

However, financial troubles would beset Hakim, bringing his ambitions for an art cinema circuit to a premature end. On the 8th September 1934, several newspapers reported that “a receiving order has been made on a creditor’s petition against Eric Hakim, film producer, of Portland Place, London”. Bankruptcy proceedings were in motion. Creditors were to meet on 19th September, with a public examination on 11th October. Just over a week later on 17th September Hakim came to Leeds for the Academy’s one-year anniversary, where he celebrated the success of the Leeds venue. The YEP reported on the event (inaccurately labelling Hakim as managing director):

Mr. Eric Hakim, managing director of the Academy Cinema, London and Leeds, entertained members of the Press and educational service of the city at lunch at the Queen's Hotel, Leeds, today, to mark the occasion of the first anniversary of the "repertory" film movement in Leeds. ‘I’m glad to say that the Academy has the hallmark of success’ said Mr. Hakim. (YEP 17 Sept 1934)

In the Alec Baron archive, the Academy Leeds flyers don’t go beyond 1934, but newspaper archives show that repertory programming continued at the cinema into 1935. It’s likely that Hakim’s involvement ended following his bankruptcy at the end of 1934, but repertory programming continued sporadically throughout 1935 under the helm of local cinema manager E. G. Pettet. Pettet would eventually leave the Academy in December 1935 to manage a cinema in Derby. Hakim sadly was not able to find his way out of debt: he was declared bankrupt again in 1947 and spent three periods in prison on fraud-related charges in the 1940s and 50s.

The Yorkshire Post on Tuesday 23 June 1936 announced a new policy and a change of name from the Academy to The Tatler, with the cinema to be run as a news theatre. The cinema remained closed for six months, undergoing significant alterations and decoration, and re-opened on 23rd December as the Tatler News Theatre.

Cohen’s 1938 plans

There would be one last attempt to establish a repertory cinema in Leeds in the 1930s. Local newspapers reported in April and May of 1938 that a repertory cinema was to open later that year led by Elsie Cohen, showing foreign-language films and revivals: “It was Miss Cohen's intention to develop a chain of repertory cinemas throughout the country, of which the Leeds cinema would be the first in the provinces” (YP 13 May 1938). Once again, Leeds was chosen as the primary provincial location, with Cohen leading the expansion this time. Cohen was planning to either acquire an existing cinema in Leeds or build a new one. By December, her plans were nearly complete, with Cohen coming to an arrangement with the Tatler cinema, and a date of January 9th 1939 set for the opening:

The idea of the new venture is to build an intimate little cinema which will be unique to the city. Miss Cohen believes that every large provincial town contains a considerable number of people who have no time for lingerie dramas and boop-a-doop comedies. She believes there is a demand for the intelligent and the beautiful on the screen, and she is out to cater for it (YEP 17 Dec 1938).

Cohen’s continental policy at the Tatler launched with a screening of Katia, a French-made historical drama starring Danielle Darrieux as a Russian princess. A series of French films, including La Grande Illusion, were screened at the Tatler until June when the YEP reported the end of its continental policy. The reason given was budget, with the tax on international film stock increasing to a prohibitive level, but it was hoped the continental policy could resume later in the year. Unfortunately, the war brought an end to Cohen’s plans for regional expansion. During the war Cohen worked for the Entertainments National Service Association, coordinating the recording and distribution of entertainment broadcasts for the British armed forces. The Academy Cinema Oxford Street closed in 1940 due to bomb damage and re-opened in 1944, sadly with Cohen no longer in charge.

Stuart Davis, Eric Hakim and Elsie Cohen all played instrumental roles in bringing art and international cinema to the UK and helped to develop its burgeoning audience in Leeds. These exhibitors laid the foundations for an independent film culture that would continue to grow after the war, and they cemented Leeds’ reputation as a key centre for art cinema outside of the capital. Following the closure of the Academy, Leeds was once again in need of a dedicated art cinema. In 1946 the Leeds Film Society was established, taking up the role of screening international films rarely seen. Fittingly, the first home of the Film Society was the Academy’s old space, the Tatler Cinema on Boar Lane, and was launched with a screening of Citizen Kane. In the next post I take an in-depth look at the history and programming of Leeds Film Society, and its relationships with the British Federation of Film Societies and the British Film Institute.

References

Untitled typed document on the history of the Leeds Film Group, Alec Baron Archive, BC MS 20c Theatre, Baron/Box 1, University of Leeds Special Collections

Alec Baron’s unpublished memoir, 1991, Alec Baron Archive, BC MS 20c Theatre, Baron/Box 13, University of Leeds Special Collections

Savoy Repertory programmes, Alec Baron Archive, BC MS 20c Theatre, Baron/Box 8, University of Leeds Special Collections

Academy Cinema Boar Lane programmes, Alec Baron Archive, BC MS 20c Theatre, Baron/Box 8, University of Leeds Special Collections

Elsie Cohen, ‘The Continental Film in England’, Sight and Sound Winter 1932/33, page 113

Elizabeth Coxhead, ‘Towards a co-operative cinema: The Work of the Academy, Oxford Street’ in Close Up, 1927-1933 : Cinema and Modernism (London: Cassell, 1998)

Stuart Davis, ‘Making Repertory Pay’, The Bioscope, 27 February 1929

Allen Eyles, ‘Cohen, Elsie (d. 1972)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004)

Paul Rotha, ‘The Unusual Film Movement’, Documentary News Letter, June 1940

Anthony Slide, interview with Elsie Cohen, The Silent Picture, Summer-Autumn 1971, reprinted in Picture House, no.20, Winter 1994/5

‘The Gloomy Screen’, Yorkshire Post, Thursday 17 January 1929

‘Repertory Film Theatres’, Yorkshire Post, Monday 21 January 1929

‘A Repertory Cinema’, Leeds Mercury, Tuesday 22 January 1929

‘The End of the Repertory Cinema’, Yorkshire Post, Tuesday 01 October 1929

‘The Savoy and it’s Public’, Yorkshire Post, Tuesday 08 October 1929

‘Men and Movements’, Kinematograph Weekly, Thursday 27 Feb 1930

‘Girls Who Need Careful Affection’, Leeds Mercury, Thursday 17 November 1932

‘The Film Public at Fault’, Yorkshire Evening Post, Saturday 01 July 1933

‘Unusual Films. New Project at a Leeds Cinema’, Yorkshire Evening Post, Monday 04 September 1933

‘Provincial Repertory’, Cinema Quarterly, Vol 2, no. 1, Autumn 1933

‘Public Notices’, The Times, Saturday November 4th 1933

‘A Pioneer of the Pictures’, Yorkshire Evening Post, Saturday 04 November 1933

‘Eric Hakim’s Future. Extension of Activities’, Kinematograph Weekly, Thursday 09 November 1933

‘Elsie Cohen and The Academy’, Cinema Quarterly, Vol. 2, No. 2, Winter 1933-34

‘Round the Show World’, The Era, Wednesday 14 February 1934

‘Repertory Films’, Yorkshire Evening Post, Monday 17 September 1934

‘New Policy for Leeds Cinema’, The Yorkshire Post, Tuesday 23 June 1936

‘Leeds Repertory Cinema’, Yorkshire Post, Friday 13 May 1938

‘Continental Films For Leeds’, Yorkshire Evening Post, Saturday 17 December 1938

‘Change at the Tatler’, Yorkshire Evening Post, Saturday 03 June 1939